The conventional venture capital funding path – from raising an institutional Seed, Series A, B, C, D, E, etc, all the way to exit via IPO – has long been treated as gospel. Its verses are most heavily preached by VC board members, whose business model it also supports.

But there is an influential tide of founders on the rise that is opting out of this path and quietly plotting a new one that leads to building generational companies.

It’s a hybrid path, combining the growth of targeted venture funding with the durability found in bootstrapping (i.e. profitability). It’s a path with less venture capital and more self-reliance.

And it’s the direct result of founders emerging from a tumultuous period of feast (with 5x more venture capital offered to startups over the past decade) and a brief flirtation with famine from the recent pullback that has left some venture-dependent companies in starvation mode.

For many founders, a steady reliance on venture capital, as it is heavily prescribed today, is often seen as unhealthy, if not risky.

Increasingly, these founders are seeking freedom from the risk and control of the perpetual pursuit of venture capital. Instead, they’re ready to reroute their time, efforts, and attention to building enduring companies on their own terms.

These founders are choosing to raise less and build more.

“Foie gras” venture capital

The clearest trend in the venture industry over the past decade is VCs offering startups more money.

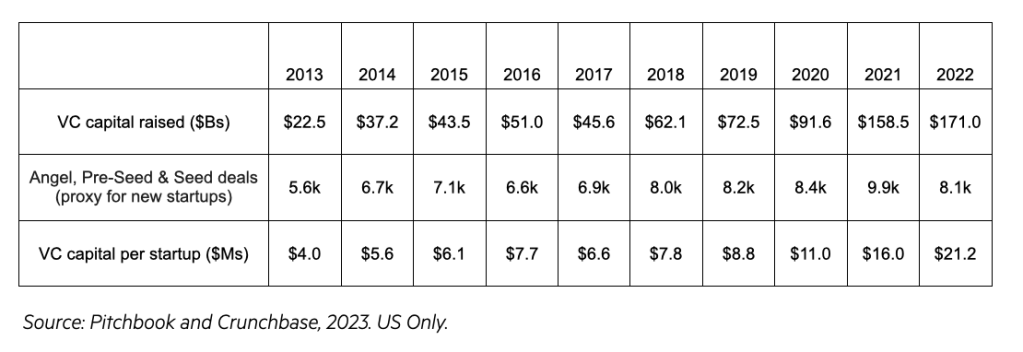

To gain visibility into this trend, we can examine the ratio of VC capital raised to new startups in any given year. An imperfect but close proxy for viable new startups is the annual number of Seed deals (inclusive of Angel, Pre-Seed, and Seed deals). When you take total VC dollars raised, divided by the number of new companies, you’ll see the average startup today has 5x more VC capital available than its counterpart did in 2013:

The primary driver of this trend is VCs increasing their fund sizes, particularly larger firms. Nearly every single major fund has implemented this change. No other strategy has been so universally adopted.

As a result, every single type of round, from Seed to Series C on, has also increased in size. Here are some averages over time:

While 2023 will likely prove to be a down year for total VC capital raised, both the average and median fund size will remain up. The average fund size went from $336M in 2020 to $386M in 2022 to $538M in 2023 (PitchBook). The trend has become the new baseline.

More isn’t always better

Why is this trend so pervasive?

Do today’s startups need more money?

Well, no.

The main driver of a startup’s burn is salaries. Salaries over time have increased, but not by 5x (the rate VC capital has increased). Even the new increased infastructue costs with AI will ultimately come down as companies scale and the industry matures. None of this justifies the rate and breadth of this capital increase from VCs.

Contrary to popular myth, statistically venture backed startups aren’t staying “private longer,” either. Between 2011 and 2021, the median time from venture funding to IPO exit in the US has fluctuated between 5 and 7 years, with no visible increase in time (Statistica 2023). Granted, SPACs may have impacted these numbers, but it’s nonetheless interesting that the data does not align to the myth.

Do bigger funds perform better?

Again, no.

Smaller funds consistently outperform large funds (on a multiple basis). More on this, below.

Does giving a startup more capital make it reliably perform better?

Another no. There is no conclusive data to support this. There is no empirical study that I know of that suggests that raising more capital increases a startup’s odds of success.

Looking at case studies, for every Stripe ($8.7B raised), there are countless startups who raised too much and did not make it. To avoid speaking ill of the dead or the fatally wounded, I’ll withhold names (the headlines will tell this story).

The lack of conclusive evidence seems to have had little impact on the VC bias that startups – as a general rule – should raise more VC capital.

Consider some of the more persuasive funding conventions prescribed by VCs:

If you can, raise more capital as opposed to less capital

- For founders, the case for more capital is easy to hear – hire faster, be offensive, save for a rainy day. But too much capital, especially too early, can depress urgency and innovation, all while contributing to unnecessarily high headcount and burn. These can be company killers. For every Figma, who raised a large but not unreasonable Seed round (for its time), there is a Seed company that raised that mega round (read $10M), which may do them more harm than good. Once you’ve raised for multiple years of runway, including hiring well and adding a buffer budget, what is any extra capital really doing? Who is that mega round really serving?

Raise at every round, or when you have explosive growth

- For many founders, taking on regular capital can be extremely valuable, as can taking on capital for hyper growth. But for startups that are already profitable and growing, raising can be a costly distraction. It can swallow founder time during company-making moments, resulting in potential loss of discipline, premature hiring, and unnecessary spending. It also can alert competition, hinder hiring (via ‘less attractive’ stock options), impact dilution, and potentially even affect board composition. Companies like Vanta chose to delay Series A to focus on building instead of raising, with others raising their huge Series As at the ‘standard’ time, because they ‘should,’ before fading into history. You have to wonder – how many of those momentum Series A companies would still be around if they just chose to build (profitably) instead of raise?

Prioritize growth over profitability to achieve outlier success

- For many founders, opting for growth over profitability has clear advantages: you can hire more, build more, market more; in short you can be generally more offensive. But for founders with the goal of creating a sustainable and durable business, prioritizing profitability growth over growth-at-all costs makes more sense. During a time when VCs were fawning over him, Ivan at Notion famously told investors that he’d “prefer to raise from his customers” as opposed to taking outside capital. Countless high-potential startups would still be around today if they had the same discipline.

VCs sell a product to founders. That product has ballooned over time in ways so that it can now potentially do harm. Like any other consumers, it falls to the founders of the companies to understand what they’re buying, and why it’s being sold in a particular way.

Foolproof rich

Here are the economics and incentives of the VC funds and why funds tend to grow over time.

The bigger the fund size, the more GPs get paid. A typical venture fund has a 2% management fee, paid irrespective of performance and based on fund size, and 20% carry, based on return of capital.

Consider this simplified model:

- A $100M fund which does 4x earns the GPs $80M ($60M in carry, plus $20M in management fees)

- A $1B fund which does 1.5x earns the GPs $300M ($100M in carry, plus $200M in management fees)

A large, poorly performing fund (1.5x) pays its GPs dramatically more than a smaller, higher performing (4x) fund. Stunningly, the large fund GPs would earn dramatically more on simple management fees alone (i.e. even if the fund was 0x, the GPs earn $200M). Granted, the $1B fund may have more GPs, but the payout differential is eye opening.

Further, smaller funds historically achieve higher returns than larger funds. For example, funds with $200M in AUM (assets under management) or less have an average top decile IRR of 62% over that last 10 years (2010-2020), versus funds with $1B-10B with an average top decile IRR of 27% (PitchBook). That’s more than a 2x difference.

With a larger fund, GPs are opting into a model that will likely yield poorer returns, but certainly pay them more.

Across investment management, the larger the AUM, the lower (yet hopefully more stable) the returns, the more management tends to be paid. It’s not controversial, but it does have implications for founders:

When that large, multi-stage VC offers you a term sheet with 2x the capital than all the other term sheets – pause.

That larger sum of capital might be the right thing for your company, or it might not be.

But it is certainly the right thing for that VC’s business model.

Raise less, build more

After watching their peers fall victim to excess (from too much capital) and more recently to starvation (from too little VC capital with the recent pullback), more founders are questioning the wisdom of the current conventional venture funding path.

Instead of treating venture as a default, founders are going back to first principles and asking new questions:

What, exactly, is the right fundraising strategy for my company? What options exist?

Today, there is a growing common awareness amongst founders that a VC-only path can put them out of business, from either too little capital or pressure to take too much capital. If their company doesn’t exist, the chance of success is zero. On the other hand, if they are constrained by just profitability, they might not be able to build what they need to build, or others can outrun them. Bootstrapping alone can also impede.

I’ve had similar conversations with dozens of founders on this topic, and I’m seeing them quietly start to pursue a new path – one that doesn’t perfectly fit within the lines prescribed by Sand Hill Road.

They are seeking to combine the growth of targeted venture funding with the durability found in bootstrapping (i.e. profitability).

Their goal is to build a viable business first, while also harnessing the growth, network, and brand benefits of strategically raising capital from top investors.

It’s a new hybrid path, and one that maximizes their odds of survival and breakout success.

Bootstrapping ethos encourages becoming profitable early, or having a path to profitability – which makes it more likely a company will stick around independent of venture capital. While targeted venture brings appropriate capital for growth as well as access to the networks and brand signals brought by top investors.

Practically, these new principles are translating into the following tactics:

- Raising a seed round with the primary aim of becoming profitable (as opposed to the primary aim of raising a Series A)

- Raising a venture round from a top fund, gaining one top board member, but from there, opting out of raising a series of rounds

- Raising smaller, disciplined amounts of capital, or delaying raises if the company is profitable and growing well

In the past, some of these tactics were seen as controversial, if not renegade. Going forward, I see a groundswell movement and eventual wide-scale practice of this approach. We’ve already seen standout companies over the past 15 years – including Notion, Zapier, and Vanta to name a few – implement portions of these tactics to great success.

More startups will adopt this approach as they come to understand its advantages, including:

- A more disciplined, focused culture: Operating with financial constraints instills a culture of fiscal literacy and responsibility throughout the organization. It also primes creativity and inventiveness.

- A sharper, more coordinated product: To keep customers paying, companies must keep customers delighted. A mandate to generate compounding revenue sustains pressure on product teams to listen to their users, understand the wider market, and craft a beloved product. It also forces product and engineering teams to work in concert with sales, marketing, and support on a common goal.

- More control, ownership, and upside: Founders will likely retain authority on everything from company decisions to exit scenarios. For example, less capital creates less of a preference stack for founders and employees on M&A exits; it’s also more likely to ensure founder control of the exit decision, including whether to go public.

It yields all these benefits without sacrificing the growth and value brought by VC funds.

Founders who choose to raise less are liberating themselves from the venture hamster wheel, and in the process, are giving themselves more power to build generational companies.

In short, the “raise less, build more” approach empowers founders to be builders again.

And that makes for better products, better teams, and better, more valuable, companies.